The unexpected ingredient for positive conflict

No matter how well we plan, how hard we work on communication, how much time we put into collaboration. Conflict happens. In our life challenges arise, opinions differ, and tough questions will need to be answered.

But what if these situations didn’t need to be a struggle? What if these challenges don’t need to result in conflict?

Neuroscientist Beau Lotto conducted an ambitious study with Cirque du Soleil on the emotion of awe and its psychological and behavioural benefits. It offers a really interesting way to approach situations that could lead to conflict.

The need for closure and certainty

In a recent Ted Talk Lotto spoke about our fundamental need for closure and uncertainty:

“We hate uncertainty. We hate to not know. We hate it. Think about horror films. Horror films are always shot in the dark, in the forest, at night, in the depths of the sea, in the blackness of space. And the reason is because dying was easy during evolution. If you weren’t sure that was a predator, it was too late. Your brain evolved to predict. And if you couldn’t predict, you died. And the way your brain predicts is by encoding the bias and assumptions that were useful in the past.”

So when we encounter a situation, a person, or a challenge, we encounter it with bias and assumption. We create the meaning and the interpretation and project that onto it.

Put yourself into uncertainty and that physiological and mental response is magnified. As Lotto puts it:

“We often go from fear to anger, almost too often. Why? Because fear is a state of certainty. You become morally judgmental. You become an extreme version of yourself. If you’re a conservative, you become more conservative. If you’re a liberal, you become more liberal. Because you go to a place of familiarity.”

But across all parts of our lives, we can’t avoid situations of uncertainty and encounters where we might come across conflict.

So is there a way we can enter them in a state that allows us to be more open and avoid taking shelter in our place of familiarity?

Enter the power of awe…

The awe factor

It might sound unlikely, but the experience of awe can help us get to a place where our mind is open and we can be comfortable with feelings of uncertainty.

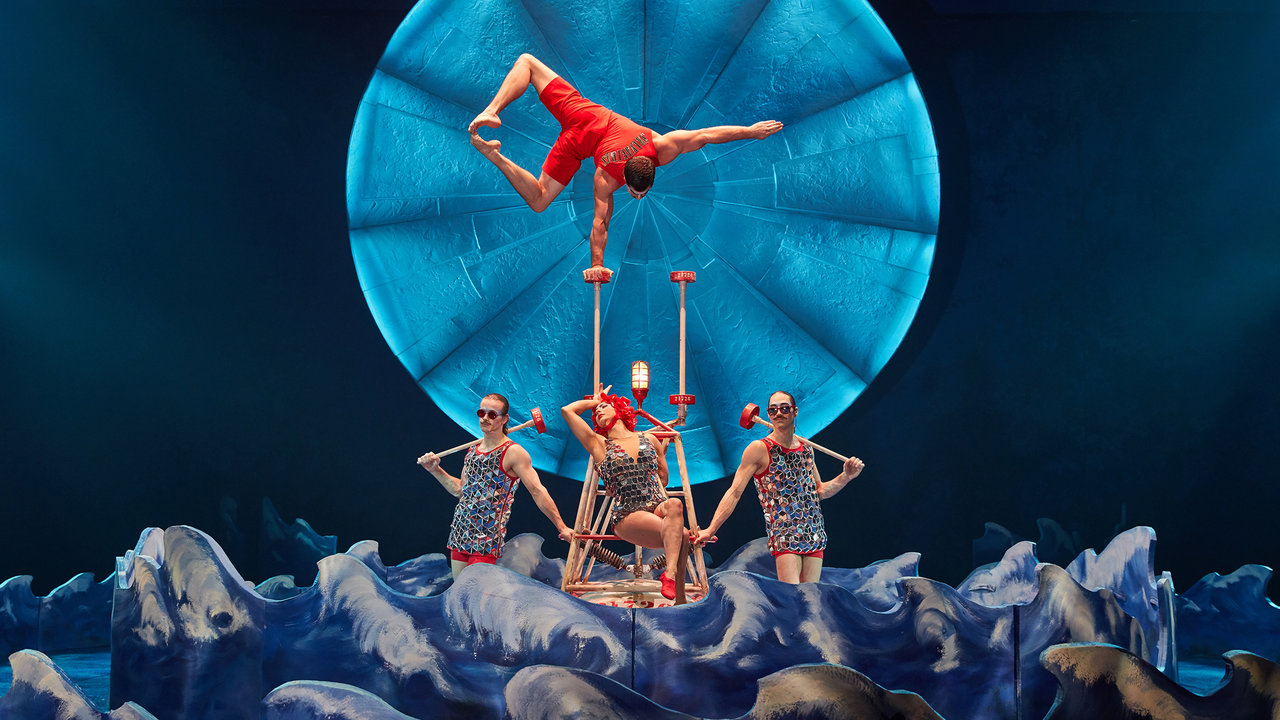

Lotto carried out some fascinating research recording the brain activity of people watching Cirque Du Soleil.

The study found that when audience members experienced higher levels of self-reported awe, there was reduced alpha wave desynchronisation in the prefrontal cortex. Higher awe was also correlated with decreased activity in the default mode network. Respondents also experienced asymmetric activity in the prefrontal cortex.

Essentially, when you’re experiencing awe the part of your brain responsible for executive function and attentional control is less active and the part of your brain that is active during creative ideation, divergent thinking, and daydreaming is more active.

As Lotto says:

“We’ve also shown in this study that people have less need for cognitive control. They’re more comfortable with uncertainty without having closure. And their appetite for risk also increases. They actually seek risk, and they are better able at taking it.”

In his Ted Talk he also refers to a comment from photographer, Duane Michaels, who said that the secret of awe is that it gives us the curiosity to overcome our cowardice.

Using awe as an approach to conflict

Think about a time when you were in conflict. It could be a time you had a different view to a fellow leader on your growth strategy, it could be a time when you had a wildly different opinion on an appropriate curfew for your teenage son. Did you approach the situation intent on proving you were right and attempting to shift opinion to meet yours?

Awe doesn’t have the power to rid our lives of conflict, but it could help us to come at it from a different angle.

As Lotto says:

“What if awe could give us the humility and courage not to know. To enter conflict with a question instead of an answer. Entering conflict that way, to seek to understand, rather than convince. And to understand another person, is to understand the biases and assumptions that give rise to their behaviour.”

So how can we find and use the power of awe? It’s probably not practical to call in Cirque Du Soleil to give a performance before every challenging meeting, but we can find awe in the everyday. As Lotto alludes to, it can be about scale – the sunrise, mountains, tall trees or incredible architecture. It can be found in the colour and form of incredible art or the melody and beat of unexpected music.

We can build our ‘bank of awe’ by finding more time for art, adventure, science and performance, broadening our horizons so we’re more open to new ideas and different perspectives.

And we can think about ways to help ourselves and others through upcoming conflicts. Move that board meeting from the office to a more awe-inducing setting, the coast, the mountains, a historic hall, or have a pre-meeting trip to a gallery or performance.

Everyday conflicts aren’t something to be avoided, they can help us grow and develop better ways to work and live. Think about how you can use awe to be braver, be curious and to help those around you to do the same.